Stable Roommate Problem

First, a little a history lesson:

The Stable Roommate Problem (SRP) is descended from another matching problem, the Stable Marriage Problem (SMP), which can be summarized as follows:

Given a set of n men, and a set of n women where each man has ranked each woman and each woman has ranked each man, create a stable matching with one man and one woman per pair.

A stable matching means that there are no people, x and y, where x and y are not paired, but prefer each other to their current parter. This problem has been extensively studied as it can applied in many situations, such as matching prospective students to colleges. David Gale and Lloyd Shapely presented their findings on this problem in the 1960s, not only proving that a stable matching is always possible, but also providing an algorithm to find one.

In the same paper, Gale and Shapley presented the idea of SRP, removing the bipartite aspect of SMP and generalizing it to any evenly sized graph. They use an analagous definition for stability, the only real change being that x and y are from the same set. The problem is now posed as:

Given a set of 2n participants, where each strictly ranks the other members of the set, create a stable matching.

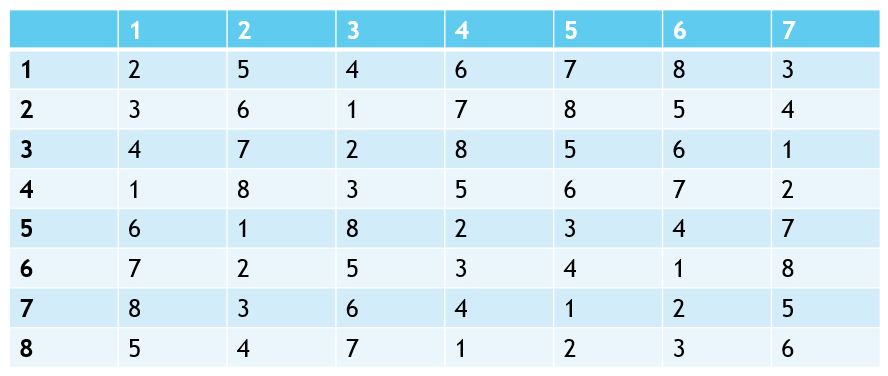

In the 1970s, Donald Knuth, in an exploration of SMP variants, demonstrated that it is possible have multiple stable matchings for SRP. In the image below, there are three stable matchings:

{{1,2}, {3, 4}, {5, 8}, {6, 7}}

{{1, 4}, {2, 3}, {5, 6}, {7, 8}}

{{1, 5}, {2, 6}, {3, 7}, {4, 8}}

He then asked whether it was possible to solve the problem in polynomial time. The answer did not come until the 1980s, when Robert Irving published an algorithm to find a solution to the problem, if it exists. This is a fairly imporant departure from SMP - a stable matching may not always be possible. It’s not difficult to construct a circumstance where this would be the case. Let’s examine two configurations of a group of friends.

| Config 1 | Config 2 |

|---|---|

|

|

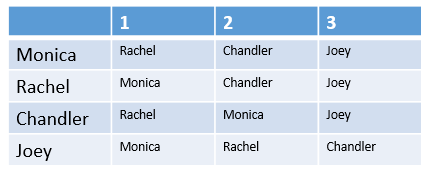

In the first configuration, we can see that a stable matching will be possible, despite the fact that Joey seems to be everyone’s least favorite (perhaps because he doesn’t share his food). Monica and Rachel can be paired together, placing Chandler with Joey. Even though Chandler would prefer to live with one of the girls, the women are so happy together, that neither one would be willing to swap roommates.

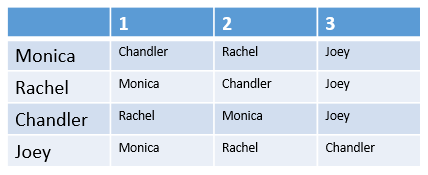

In the second configuration, things get a little more dicey. Again, we can see that no matter who gets paired with Joey, that person will want to swap roommates. The important part in this example comes from examining the non-Joey pair, which could be Monica/Rachel, Monica/Chandler or Rachel/Chandler. If we pair the women together, we fail to get the same level of bliss: Rachel would be happy, but Monica would actually prefer to be paired with Chandler, and she would be able to convince him to swap. If Monica and Chandler move in togeher, we would see that Chandler would actually try to pursue Rachel as a roomate, and again, would be successful in organizing a swap. That would leave trying to have Rachel and Chandler live together, which also would not work, because Rachel would want to live with Monica more and try to organize a swap. No matter what configuration we have, one of the people in the non-Joey pair will prefer Joey’s partner to their own and want to swap, so a stable matching is not possible.

Irving’s Algorithm

Irving’s work focuses on eliminating any pairings that would not permit a stable matching. If a stable matching can be found, then the algorithm will terminate with each preference list containing a single entry, where x will be the only member of y’s preference list iff y is the only member of x’s preference list. At any point, if a participant’s preference list becomes empty, that means that a stable matching does not exist, and the algorithm terminates.

The algorithm is broken into 2 phases. The first builds on Gale and Shapley’s work, performing a series of proposals. Although they are called proposals (due to the influence of Gale-Shapley’s work), the relationship is not mutual. If Monica holds a proposal from Chandler, it does not mean Chandler has to accept a proposal from Monica; he may still accept a proposal from his other friends, Rachel or Joey, while still proposing to Monica. In some publications, the proposals in Irving’s work are referred to (more accurately) as semi-assigments.

To perform the proposals phase, each participant goes through its preference list, proposing to each member until it is accepted. If a proposal is rejected, then both participants remove each other from their preference lists. A participant will reject a proposal from another person if they already hold a proposal from someone higher up in their preference list. Note that proposals may be rejected in later rounds; if that happens, we simply encourage the rejected party to get back out there, starting at the next spot in their list and continue proposing.

At the end of this phase, we then trim the preference lists, where each participant rejects anyone later in the list than the person who proposed to them. If there are no empty lists, we’ve resulted in something called a stable table. There are a few important properties of stable tables:

- x is first on y’s list iff y is last on x’s list

- x is not on y’s list if y is not on x’s list or if x prefers the last element on its list to y

- no list is empty

- a stable table can be obtained from another stable table by identifying and reducing rotations

- no list is empty

- most importantly - a stable table where all lists are of length one is a stable matching!

In the second phase, Irving uses rotations. A rotation is defined as a series pairs, (x0, y0),(xi+1, yi+1),…,(xk-1, yk-1), where:

- all x0…xi are distinct

- yi is first on x(i+1 mod k)’s reduced list

- yi is second on xi’s list

To find these rotations, simply start with any member who still has multiple entries on their preference list and construct these pairings until a member is repeated; this means we’ve found a cycle. Then reduce the rotation, by having yi reject x(i+1 mod k), omitting any pairs not in the cycle. This process continues until no rotations can be detected; which either results in a stable matching, or at least one member with an empty preference list.

Rotations may sound odd to keep track of, but they’re very simple when you draw them out. Create a table with 2 rows and at most n+1 columns. Choose the first participant that has more than one entry and put it in the top-left square. Then fill out the rest of the table, so that the square on the bottom is the second entry in the top square’s reduced preference list and the next square (up and to the right) is the last element in the bottom square’s preference list. Continue this pattern until a participant appears twice in the top row. Then reject diagonal (bottom to upper and right) pairs in the cycle.

Pseudocode for Irving’s Algorithm

// Phase 1: Proposals

set-proposed-to := [];

for person in X

begin

proposer := person;

repeat

proposer proposes to his next-choice;

if not rejected

then if next-choice in set-proposed-to

then proposer := next-choice’s reject

until not (next-choice in set-proposed-to);

set-proposed-to := set-proposed-to + [next-choice]

end

//trim the lists (this is sometime explained as its own phase)

for each x

y := proposal x holds

for all z that appear after y in x's preference list

x rejects z

//Phase 2 - Rotation and Elimination

next := any person in X with more than 2 entries in their list

while any preference list has multiple entries and there is no empty prefence list

i = 1

p1 := x

while p1...pi distinct

qi := second person in pi's preference list

pi+1 := last person's in qi's reduced list

i:= i+1

cycle := remove any pairings in the sequence that occur before the first repeated pi

for all pairs in cycle

qi rejects pi

qi proposes to pi+1**

if no empty preference list

for each x in X

y := first in x's preference list

if x less than y

output x matched with y

else

report no matching

Notes:

* rejections are mutual, so 'x rejects y' removes y from x's prefernce list x and removes x from y's preference list

** we will need to loop around, so the final qi will reject p1

How Fast This Works

This algorithm scales quadratically with the number of participants; note that some sources claim this is a linear-time algorithm, but that in relation to the input, which is essentially an n*n table. In a very handwavey summary, you could think of it like this: In each phase, the algorithm incurs a linear amount of overhead, and continually removes entries from the table; once an entry has been removed, it is never processed again_

To fill in a little more detail:

In the first phase of the algorithm, we’re reducing pairs of elements in the preference lists. For each proposal, we can determine whether a rejection should occur in constant time, and if so, then perform the mutual rejection in constant time. If a participant’s proposoal is initially accepted and then later rejected, we don’t start over from the top of their preference list, we merely continue from where we left off. In the worst case, we would see a high number of rejections and need have all the participants go through a high number of rejections, which would still only cost us O(n2) work.

In the second phase of the algorithm, the driving factor for the amount of work is finding and reducing the preference cycles. We know that rotations are bounded by n + 1, since we stop once an element is repeated in the top of the table. So the two worst case scenarios would be to either have a large number of rounds (but each rotation would be small), or we would have some very large rotations (but only a limited number of rounds).

If we had the smallest rotation each time, we’d be removing pairs. So we’d have n2/2 cycles, and then c*2 work per cycle. We’d still end up with c*n2 operations to process the entire matrix. On the other hand, if we had a large rotation each time, we would have n2/n rounds, with n*c work to reduce the rotation each round. Again, we’d end up with an O(n2) result in this scenario.

The important part here is that the preference lists are reduced in each round AND that in order to find and reduce rotations, we only process through a small number of elements at a time.

Demonstration

There is a demonstration that accompanies this writeup. It currently has 3 examples pre-programmed. Use the left and right arrow keys to traverse through the algorithm’s operations. At any point, you may hit 0, 1 or 2 to change the example. It is written in Processing; I’ve included a link to an in-browser demo.

Note: mainly due to the way that state is saved (since we copy over several n*n arrays), this implementation incurs a lot more overhead than Irving’s algorithm. This is much closer to O(n4) overall.

Variants

Incompletion and Indifference

In the original problem, each member must provide a strict ranking of all other participants - the two main twists on this problem deal with relaxing these restrictions. The first is allowing imcomplete lists - participants may provide strict rankings for only some of the other members of the set; any member they do not rank is deemed unacceptable. This may result in an incomplete matching (some participants may not end up in a pair). If there are multiple stable matchings, Irving and David Manlove were able to prove that every possible verion will have the same number of pairs. Irving’s original algorithm will also suffice for this variant (with the overall complexity scaling linearly with the number of pairs in the matching).The second is to remove the requirement for strictness in ranking, and allow for ties in preference lists(this is also called indifference). Combining both of these variants is called SRTI.

When exploring these two problems, the definition for a stable matching also gets tweaked, and is split into the three following levels:

-

weak stability - there are no two participants, x and y, each of home is either unmatched, and finds the other acceptable, or strictly prefers the other to his partner. An interesting impact of ties onthis type of stability (regardless of completeness for preference listss) is that is becomes an NP-hard problem (proved by Eytan Ronn), even if there is only a single tie per list and each tie only consists of a pair of elements.

-

super[-strong] stability - there are no participants, x and y, each of whom either is unmatched and finds the other acceptable, or strictly prefers the other to his partner in m or is indifferent between them. If this kind of matching exists, it can be found in O(n) time, thanks to a result by Irving and Manlove.

-

strong stability - there are no no two participants, x and y, such that x strictly prefers y to his partner in M and y either strictly prefers x to his partner in M or is indifferent to them. Sandy Scott presented an algorithm that solves this problem in O(n2) time (note - if you actually examine his paper more closely, he demonstrates that it scales not with input size, but the number of pairs in the matching). Adam Kunysz has also submitted an algorithm that can find a solution in O(n*m), where m is the sum of all the lengths of all the preference lists.

There are also different kinds of optimality to consider in SMP (and variants like SRP explore), which are usually based on how each partner ranks their mate in the matching. This would likely be sufficient material for another project (although that’s not my call, just a suggestion). For a quick reference, two kinds of optimality that apply to both problems are egalitarian, where both partners has ranked each other as equally as possible, and minimum regret, which tries to ensure that each person gets their highest choice possible. There are more that apply to SMP due to the bipartite nature of the problem (such as skewing one set’s prefences to count more in the matchmaking process).

Triples

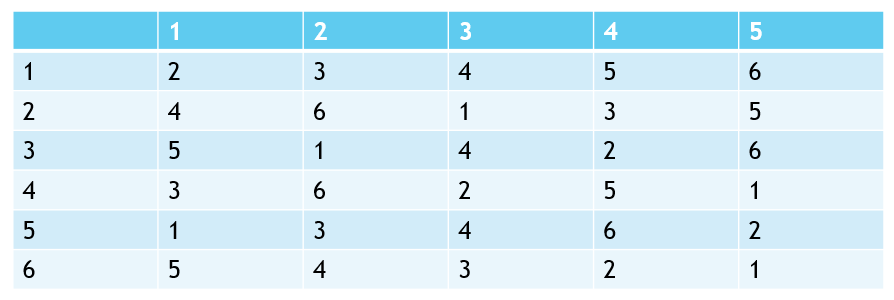

Another variant that’s worth checking out is the 3D SRP, which is Stable Roommates where we try to break the set into triples instead of pairs. Researchers in Japan has shown this to be possible, but solving the problem is NP-hard. The following image is an instance where a stable matching of {1, 3, 5} and {2, 4, 6} can be found; like the original problem, it is possible that a stable matching does not exist.

Sources

- Irving’s Algorithm - https://uvacs2102.github.io/docs/roomates.pdf

- Donald Knuth - Stable Marriage and its Relation to Other Combinatorial Problems (translated by Martin Goldstein)

- Sandy Scott - http://www.dcs.gla.ac.uk/publications/PAPERS/8482/thesis.pdf

- Adam Kunysz - http://drops.dagstuhl.de/opus/volltexte/2016/6401/pdf/LIPIcs-ESA-2016-60.pdf

- Kazuo Iwama, Shuichi Miyazaki, Kazuya Okamoto - https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228816339_Stable_roommates_problem_with_triple_rooms